The rains have come for Sydney, finally

Dam Levels

Water NSW puts out water storage reports every Thursday. The most recent report captured a record-breaking rainfall in the Greater Sydney area, quenching the water shortage that’s been building since about 2017. With a week’s worth of rain, dam storage levels nearly doubled from 41.8% to 75.1%.

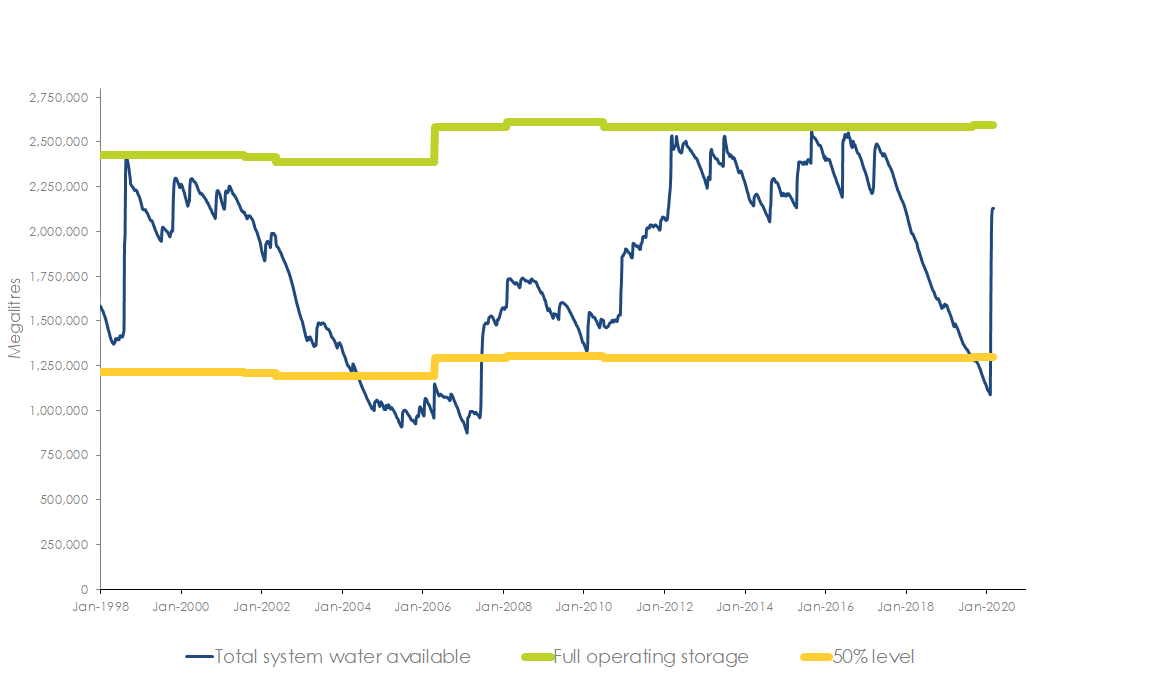

As part of the weekly reports, Water NSW also publishes a graph of the historical total water storage levels in Greater Sydney. The only gotcha with this graph is that it doesn’t show rainfall exactly - only the amount of water that ended up in dams around Sydney. You can’t spot the difference between a small rainfall right on top of a dam, and a big rainfall that didn’t make it into any dam at all.

This graph tells a story or two. The most recent rainfall is captured in the big spike on the far right of the graph - easily the biggest weekly inflow since the turn of the century. Ironically, the dryness of the land might have actually increased the amount of inflow. Too-dry dirt can’t properly absorb water, allowing it to run off into streams and rivers, and then on into the dams.

Right next to it is the effect of the most recent drought on Sydney’s water levels. Another historic event, this time a dry period leading to a steep decline in stored water, faster than anything in recent memory. The rains came as new mitigation strategies were being annouced, like the expansion of the Sydney Desalination Plant.

The NSW Government announced their expansion plan of the Sydney Desalination Plant after dam levels fell in 2019 to below 45%. After dam levels fell. We’ve waited until we reached the lowest dam levels in over a decade to start the planning and construction process. Lucky it rained.

Mitigation Strategies

The trouble with our current methods for drought-proofing is that they’re not preventative - they’re almost always reactive. Why are so many of our drought-proofing strategies, especially in Sydney (and NSW), planned and announced at the peak of the drought?

I think there are two main reasons.

Firstly, it’s tough to justify a massive capital investment without some urgent need or quantifiable benefit, e.g. a desalination plant that will sit mostly idle until dam levels fall far enough. Even though the desal plant has a benefit - that being covering 15% of Sydney’s water needs - it’s not quantifiable in the sense that we don’t know for sure when that benefit will be realised. The lack of urgency in the good times means that other, more urgent projects could receive funding preferentially. The lack of urgency also relates to the next reason: political impact.

This might be too cynical, but I would guess that there’s an optimal time politically to annouce mitigation measures, and this time is likely well into the drought itself. Too early and it’s not on the public’s radar, not relevant enough. Too late and it might be seen as poor leadership reacting too slowly. Just right, as awareness starts to reach critical levels, and it makes the announcing government look as good as possible.

I’m sure that the time it takes to plan, approve, finance, tender, design, and construct drought-proofing measures is another massive contributing factor. Government projects tend to take a lot of time. The first feasibility study for the Sydney Desal Plant was undertaken in 2004, 6 years before completion. But this process could be started at any point, not just when it’s looking like we might need them. Drought mitigation could be another example of the agency problem in politics.

Obviously not everything we do is reactionary. Water restrictions are rightly only implemented in shortages. Construction of the Sydney Desal Plant went ahead even after the breaking of the drought. In fact, the plant was designed with potential future expansion in mind. In both of the past two droughts we’ve been bailed out by rain mid-implementation of mitigation. But what happens when we have an even more extreme dry period, with no timely rains? Will we be prepared?